INSIDE SHAKESPEARE AND COMPANY 12 RUE DE L'ODEON

LA MAISON DES AMIS DES LIVRES 7 RUE DE L'ODEON

CHARLOTTE RAMPLING EN VESTE MOICANI DANS LE MAGAZINE ELLE DU 23 SEPTEMBRE 2016

Charlotte Rampling porte une veste Moicani page 134 du Elle du 23 septembre 2016

CHASING SYLVIA BEACH

OU TROUVER FABIANA FILIPPI A PARIS : A LA BOUTIQUE MOÏCANI 12 RUE DE L'ODEON PARIS 6EME

JUPE OU PANTALON ?

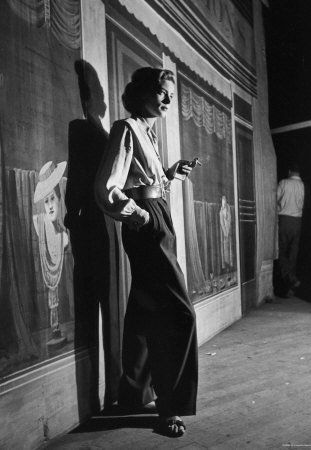

BORDERLINE DIRECTED BY KENNETH MACPHERSON (1930)

Fiche technique

- Réalisation : Kenneth Macpherson

- Pays d'origine : Royaume-Uni

- Scénario : Kenneth Macpherson

- Producteurs : Bryher MacPherson et Kenneth MacPherson

- Société de Production : Pool Group

- Lieu de tournage : Suisse

- Format : Noir et blanc - muet

- Durée : 1heure 15 minutes

- Date de sortie : Royaume-Uni 13 octobre 1930 Belgique 13 octobre 1930

Synopsis

Thorne and Astrid are a white couple, he an alcoholic, she a neurotic. Pete and Adah are a mixed-race couple. Thorne, Astrid and Adah are staying at a room in a non-specific European location.

Thorne has been having an affair with Adah, who has become separated from her husband. Adah finds out that Pete has been working in a hotel café in the town and they resume their relationship. When Pete and Adah are reunited, tension erupts between Thorne and Astrid.

Thorne eventually decides to leave Astrid but, when she tries to stop him, he accidentally kills her in the ensuing tussle. Meanwhile, Pete is subjected to racist comments from Astrid and an old lady. After the death of Astrid, these racist feelings lead to Pete being ordered out of town, while Thorne is acquitted of murder.

(Borderline is a 1930 experimental silent film by Kenneth MacPherson and the Pool Group, starring Paul Robeson. In the film two couples-White and Black-intersect with racial values, each other, and the small town in which they find themselves. The Pool Group consisted of Winfred Ellerman, her bisexual husband Kenneth McPherson and her lover (and Kenneth MacPherson's), the poet H.D. (Hilda Doolittle). Borderline was the last film that the POOL group would complete before disbanding and has become a classic of early experimental cinema.

Adah, a black woman, has an affair with Thorne, a white man, much to the dismay of some of the prejudiced townsfolk and Thorne's wife, Astrid. Adah attempts a reconciliation with her man, Pete, but eventually leaves him and the town. Meanwhile, Astrid goes mad and cuts Thorne's face and arm with a knife, but then mysteriously dies. Thorne is tried but acquitted. Because of the events, the mayor sends Pete a letter asking him to leave town for the good of all concerned.

The border town scenes were shot on location in Switzerland. Real-life partner Essie Robeson co-starred with Paul in this avant garde film which was never shown in public theaters. The filmmakers was most concerned with avant garde film technique and unconventional editing, though one critic who did notice the film noted that in the character portrayal, "Borderline is an attempt...to treat the Negro as a sensitive and intelligent being."

For many years, the film Borderline was largely inaccessible to film scholars, with rare copies in a few archives around the world and seldom screened in public. Many film historians of avant-garde and experimental film-making, feel that it represents one of the last, examples of modernism of the 1920s, when many artists had hoped that artistic experimentation and commercial viability need not be mutually exclusive. For feminist literary modernists, it is not only the film that H. D. starred in, but it also serves as a study imbued by her unique aesthetic vision. Highly influenced by the psychological realism of GW Pabst and Sergei Eisenstein's complex montage format, Macpherson embellished this story by portraying the extreme psychological states of the characters.

A booklet that Macpherson and Doolittle wrote to accompany the film concentrated not on narrative coherence but on psychological metaphors. Macpherson was also influenced byHans Sachs, Winfred Ellerman's analyst at the time of filming. The booklet became a piece later published in the Pool Groups' literary journal, Close Up

(WIKIPEDIA)

A ground-breaking film for its treatment of race and sexuality,Borderline (1930) was directed by Kenneth Macpherson, editor of the influential intellectual film journal Close Up (1927-33), the first British journal dedicated to film as a modernist art form.Macpherson had previously made three short films, but this was his first feature and by far his most ambitious effort.

Borderline stars the poet H.D. (real name Hilda Doolittle) andMacpherson's wife, writer Winifred Bryher, both on the editorial board of Close Up, as well as the black American actor, singer and political activist Paul Robeson and his wife, Eslanda Robeson. The narrative is relatively simple, depicting an inter-racial love triangle, but Borderline's attempts to portray the extreme psychological states of its characters render it a quite complex film.

The film concentrates on the inner states of its protagonists, using a technique that H.D. referred to as 'clatter-montage', in which rapid montage combinations create an effect close tosuperimposition. This method was inspired by the editing methods used by Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, yet the film's attempt to probe psychological states was more directly inspired by the German filmmaker, G.W.Pabst.

The film also probes racial issues. Pete (Paul Robeson) is black, while Adah (Eslanda Robeson) is described by the film notes as being 'mulatto'. Pete, who is married to Adah, visits his wife at an inn, where she has been having an affair with Thorne (Gavin Arthur), who is also involved with Astrid (H.D.). Here he encounters racial prejudice from Astrid as well as an old lady. After Thorne has accidentally killed Astrid, Pete is forced out of town, while Thorne escapes punishment, thus underlining racial inequality. Although Pete and Thorne are reconciled at the end, the unfairness of their treatment remains.

As well as its explicit themes of racial prejudice, Borderline also contains an implicit homoerotic subtext. Although there are no overt references to homosexuality, the topic is alluded to in some of the performances. Marginal characters, such as the manageress and barmaid at the inn, have an air of sexual ambivalence, while the (male) pianist is seen gazing longingly at a picture of Pete on his piano. This homoerotic view of Pete is reinforced by the way in which the camera frequently lingers overRobeson's semi-naked body. It is also worth noting that H.D. was lesbian, and is thought to have had an affair with Bryher.

Jamie Sexton

Why is Borderline being stopped at the British border?

By Sophie Mayer

On an elegant walkway in the new extension of the BFI Southbank (formerly the National Film Theatre), a copy of an earlier issue ofVertigo shares a wall-mounted glass exhibition case with a number of other film journals, including Undercut. Vertigo is in the bottom row, not as a critical judgement, but as the most recent exemplar of the critical film magazine in a lineage of British film writing. In the top left-hand corner is the small magazine that started it all - Close Up. The two magazines are exhibited, alongside other documents such as stills, publicity material, diaries, notes, video and DVD cases and other ephemera, as part of the exhibition History of Artists’ Film and Video in Britain, based on David Curtis‘ new book, that fills the Mezzanine Gallery.

It’s a significant marker of the place of avant-garde moving image work in the British canon, and specifically at the National Film Theatre, where many of the foundation events of the British moving image avant-garde took place. In the early 1970s, the NFT hosted several programmes of Expanded Cinema, as well as programmes of structuralist film, and now its new Studio and exhibition spaces will once again be given over to experimental work in screen media. And yet the inclusion of Close Up strikes an odd note in this firing of a national canon: the magazine was published from Switzerland, and included a wide range of European contributors. Two of its editors were American, and one of them - Winifried Ellerman, known as Bryher - funded the journal with her family’s shipping fortune.

The exhibition is keen to find its roots in Close Up, which extends avant-garde cinematic practice in Britain historically back by several decades, staking a claim to a British role in the flowering of the French and Spanish Surrealist, German Expressionist and Russian cinemas that inaugurated the European avant-garde. The exhibition briefly features British Surrealist David Gascoyne, who wrote a number of scripts for films that were never made (a Surrealist or Dadaist form in itself), but Close Up represents its best hope of legitimating British artists’ film and video within the historical precedent of pre-war Modernism.

Close Up, however, sought no nationalist endorsement, but rather to propound not only an international avant-garde, but avant-garde praxis and theory as a model for constituting post-national communities. In so doing, the POOL group - Close Up’s editors, Kenneth Macpherson, Bryher, and H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) - also worked to cross the ideologically-connected borderline between theory or criticism and practice, ostensibly running the journal to fund and publicise Macpherson’s filmmaking. POOL madeBorderline, released internationally in 1930, in Territet, the Swiss village where Macpherson and Bryher lived and edited the journal. It is thus a manifestation of the journal’s wide-ranging theoretical interests that still hold in cinema studies today, from the nature of black cinema to the place of psychoanalysis in film.

In the booklet that accompanies the BFI’s release of Borderline on DVD, Sukhdev Sandhu describes the film’s ambivalent relation to nationalism when he comments that the guest house where the film’s disastrous action takes place is “a metonym for the liberal nation state and its ambivalent response to the newcomers,” a black couple played by Paul and Eslanda Robeson. The significance of Robeson’s appearance in Borderline is hard to appreciate in 2007, when George Clooney plays ‘one for me, one for the studio’ to both commercial and critical plaudits. While African-American stage performer Josephine Baker made several films in Europe, film performers such as Marlene Dietrich and directors such as Joseph von Sternberg were expected to travel in the opposite direction, gravitating towards the commercial centre.

Robeson, like Baker, is said to have travelled in Europe to engage with artists and communities less institutionally and interpersonally racist than those in the US. While Sandhu gives a critical account of Macpherson’s essentialist race politics, he highlights the way in which the film rejects both racist dualisms and the dominant forms in which race relations were treated: melodrama and ‘social problem’, both of which still dominate.Borderline’s contemporaneous setting and its focus on emotive relations also challenges the place of blackness in the European avant-garde, which was deeply compromised by the association of blackness with primitivism. While, as Jamie Sexton writes in the BFI booklet, Robeson is framed by images of the outdoor world in montage sequences, it is Thorne (Gavin Arthur), the white man, who acts out of intemperate passion, sleeping with Pete (P. Robeson)’s wife Adah (E. Robeson), and killing his ex-lover Astrid (H.D.) when she tries to prevent him leaving the claustrophobic guest house.

The film could be read as an extraordinary reversal of Othello, in which - as in the play - all eyes are on the dynamic, accomplished protagonist, and the narrative works not to debase him by revealing his uncontrollable passion, but, even when he is driven out of the town for Thorne’s crime, his thoughtful compassion. Macpherson described Borderline as “an attempt to take film ‘into the minds of the people in it’,” (Sexton). In place of Shakespearean soliloquies, the film derives a language of montage from the work of Pabst and Eisenstein, both of whom had been examined, and praised, extensively in Close Up. H.D. referred to the technique as ‘clatter montage’. Thorne and Astrid in particular are subject to this rapid-fire imaging of their histrionic mental state, and both of them subsequently act out those emotions, as if aspiring to roles in melodrama. Pete, on the other hand, is less permeable to cinematicity and formal conventions, and thus to hysteria: unlike the white characters, who wear their hearts on celluloid sleeves, Pete is not transparent. Nor is he “pure, in comparison to the degenerate whites,” as Sexton suggests.

Pete’s association with the outside world, to which he is exiled at the end of the film, has overtones of the Greek tragic hero whose banishment points to the corruption of the so-called civilization that attempted to contain him. As in Greek tragedy in its original performance, it also points to specific crises within the identity of the nation-state. Although the BFI assert defiantly that both Close Up and Borderline are part of a British lineage, Sandhu approaches the position of the film’s makers when he writers thatBorderline “is most successful as a rumour or a promise. Its obscurity… help[s] unshackle it from the dulling confines of British film historiography”. He goes on to argue that the film is fascinating because of its diegetic and extra-diegetic narratives of transnational migration of people and money. If, as Sandhu writes, actors “are inadequately theorised vectors of new social and cultural possibility,” then Robeson has to be read also as an American - and as metonymic for the American funds behind the film and journal - in relation to Europe between the wars.

Borderline’s other ‘outsider,’ Astrid, bridges the literary and cinematic communities, standing for the ‘imported’ or exilic Modernism of Americans in London and Paris. H.D., unlike the Modernist writers of the Bloomsbury set with whom she associated, embraced cinema, and its influence can be felt strongly in her post-war, post-Imagist poetry. Her essays on the association between female beauty and cinema prefigure much later feminist writing - but also explore the taboo of the female viewer’s visual pleasure in watching women onscreen. H.D.’s passion for cinema manifested itself as a desire to become a screen icon: she petitioned G.W. Pabst for the role of Lulu inPandora’s Box, but her performance in Borderline is the only surviving trace of her celluloid desires.

Astrid is a femme fatale, a madwoman in the attic whose desire for Thorne (Gavin Arthur) results in her death, and thus sets the plot in motion. She is the embodiment of the problematic of female cinematic desire, the related obverse of the queer looks addressed by the bar manager, played by Bryher, who was also H.D.’s lover at the time. It is Pete’s intervention into the guest house that awakens these currents of desire and, after his ejection, there are signs that queer desire, although returned to the closet, will persist, as the pianist (Robert Herring) places a photograph of Pete in his breast pocket. Macpherson implicitly codes the effect of his film: although seen by few, it held out a possibility of a cinema that was alternative in every sense, and made a powerful connection between the potential formal disruptions of avant-garde art and the social disruptions of queerness, blackness and femininity.

As the guardians of a ‘national’ film heritage know, policing borderlines of (gendered and raced) desire is explicitly connected to the policing of aesthetic and critical borders. At the same time as their release of Borderline, and their institutionalisation / exhibition of artists’ film and video, the BFI’s Mediatheque is offering a selected history of queer film and TV pre-Will and Grace. This ‘Secret Cinema’ will act as focus for a debate on whether the mainstreaming of (some) queer identities has marred the creativity of queer filmmakers. Borderline won’t be included in the Mediatheque, possibly because it lacks the camp humour or high-minded realism that mark the other contributions.

Yet it answered the question several years before: conventional forms document conventional identities. Borderline is a disquieting romance that forgoes both the ethics and aesthetics of Hollywood cinema, and it politicises sexuality by using Eisensteinian montage to frame it. Several decades before feminists announced that the personal was political, Borderlineargued that politics start in interpersonal relations not in defining national canons, and that form offers the most profound challenge to the cultural taboos and constructions that delimit erotic and social relations and their depiction in art.

__________________

Courtesy of Vertigo Magazine

This essay was published in Vertigo Vol 3 Issue 6

Sophie Mayer is the author of The Cinema

Borderline, 20 November 2007

Author: mangoloid from Mountains!

In the fall of 1927, a British film magazine appeared titled "Close Up." Of its purposes, it was trying to elevate film to the status of "art", it was trying to promote the educational qualities of film, it was trying to kick the British film industry into high gear (indeed, all the articles lamenting the poor British film industry grow wearisome), etc., etc. Of these purposes, it was also championing the minorities, blacks in film being one of the main focuses of this purpose.

The brainchild behind this "Close Up" was a man named Kenneth MacPherson, whose name you'll also notice under the Writing and Directing credits of "Borderline", the film in question of this review.

I watched "Borderline" because I'm a fan of this old magazine. Back in these days, the writers had a much clearer sense of film and its potentials, and their writing has a pop and vigor, the type that would transform into the raging "wit" that today's writers pass off. With MacPherson, two others edited and contributed to "Close Up". The first of these is Winifred Ellerman, pen-name Bryher. The second is Hilda Doolittle, pen-name H.D., American poet, actor in "Borderline." Other personalities, of course, frequently appear in the publication, but it is these three whom I'm quite fond of, especially the two women. Quite naturally, I had to see these personalities materialize on film, their only film.

It's amazing how well this film corresponds to these personalities I've loved. The rhythm, the technique, the good-humor of "Borderline" is so apparently theirs. Of course, I say this from bias, but I still say it is uniquely the product of MacPherson, of his person and people. And the jazz score on the Criterion disc compliments this personality well, I feel. It compliments the film. It compliments the rhythm, the technique, and the good-humor. Oh, I should probably define these. Hmm... The rhythm is difficult to describe. The cutting is strange and... jazz-like (undoubtedly, the jazz score again biases me). The story is more rhythmic than coherent, and apparently this throws people off (as evidenced by the few uninformed narrative junkies who have submitted embarrassingly bad reviews to this humble IMDb page). The technique is often impressionistic. "Borderline" is beautifully photographed, if I may say so, and the Criterion quality is the standard of excellence. The thoughtful angles, the focus and lighting, the good-humor... all shines through on the DVD. Oh, the good-humor! Well, that's something you have to experience.

I'm thankful MacPherson made a film. He should have made more. Well, anyone who's interested has some writings they can turn to. In fact, more than "Borderline" I'd like to recommend "Close Up" to the intelligent film-scholar. You'd be surprised how finely clear these writers' thoughts are and you'll get a very good look at the industry of the time (and the people who drove it). Worthwhile.

P.S. Robeson is really good, too good.

Borderline (1930)(Criterion Edition)

Borderline (1930), which shares a disc with Body and Soul (1925) on the new four-disc Criterion Collection box set Paul Robeson: Portraits of the Artist, is an experimental film directed by British film theorist Kenneth Macpherson (editor of the critical journal Close-Up). Like Body and Soul, the film combines melodramatic story flourishes and technical audacity. And it is intentionally confrontational on every level.

The story, in which Pete (Robeson) and his lover Adah (Robeson's real-life wife, Eslanda Robeson), engage in a convoluted series of interracial affairs, is aggressively provocative, and Macpherson gives it an editing style to match. The cutting is extremely fast, even disjointed at times, and this approach gives the whole movie a jittery rhythm that perfectly expresses the anxiety of its characters. Unfortunately, the film lacks Body and Soul's breadth of tone and subject, and both the style and the substance are too one-note for the movie to succeed as anything more than an intriguing oddity.

Robeson is as charismatic as ever, but Macpherson's method of imparting content through fast-cutting demands that he be more of a model than an actor. (The ensemble nature of the picture also gives Robeson far less to do than in Body and Soul.) Nevertheless, as a relic of the British avant-garde movement, Borderline has academic value, if not much entertainment value.

Though Macpherson's film, which is accompanied by an outstanding jazz score, is more a movie to be admired than enjoyed, it's nonetheless an interesting enough curiosity to warrant a look for film students and Robeson fans.

— JIM HEMPHILL

Disc Features

FEATURED ON THE DISC PAUL ROBESON: OUTSIDER WITH THE FEATURE BODYAND SOUL

- New, digital transfers of Body and Soul and Borderline created from the best surviving elements

- Audio commentary for Body and Soul by Oscar Micheaux historian Pearl Bowser

- Musical scores by jazz recording artists and composers Wycliffe Gordon (Body and Soul) and Courtney Pine (Borderline)

- Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

MONKEY'S MOON DIRECTED BY KENNETH MCPHERSON (1929)

Pool Films resulted from the creative collaboration of writers Kenneth Macpherson and Bryher (Annie Winifred Ellerman) and Imagist poet H. D. (Hilda Doolittle). Funded by Bryhers inheritance from a vast family fortune, their projects were fueled by the principals interest in film and artistic experimentation. The three were invested in developing a context in which the young medium of film might be viewed as a fine art as well as interact with other verbal and visual art forms. The Pool Films productions, which were directed by Macpherson and often featured H. D. and Bryher as actors, experimented with narrative forms and explored the use of dramatic lighting and effects such as montage to represent emotional and psychological states.

Monkeys Moon, a film featuring two of his and Bryhers pet monkeys, was thought to be lost until the Beinecke Library acquired a copy in 2008. Some eighty years later, this film has been fully restored and digitized

/image%2F2146588%2F20160917%2Fob_2ee7f2_images-q-tbn-and9gctbn6ifvy11btjcgslkm)

/image%2F2146588%2F20160915%2Fob_eb880b_telechargement.jpg)